Languages that wrap words

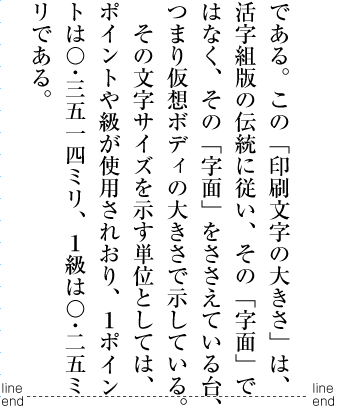

Space delimited words

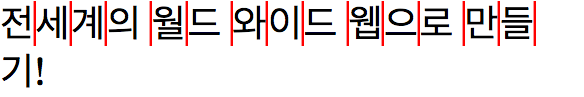

This is an approach that most people are familiar with, and it’s the way the English text in this article works. When the end of the line is reached, the application typically looks for the previous space, which is taken to be a word delimiter, and wraps everything after that to the next line*.

Of course, things can be more complicated than just finding the previous space when justification is applied to text. For example, it may be possible to reduce the inter-word spacing on a line, in order to allow a word to fit when it would naturally overflow slightly; or conversely, it may be better to choose an earlier break than the immediately-preceding space, moving a word down even though it could fit, in order to improve a following line. Read more about justification.

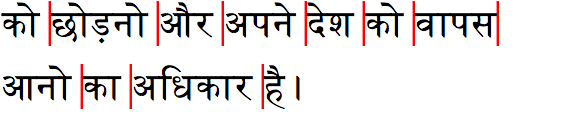

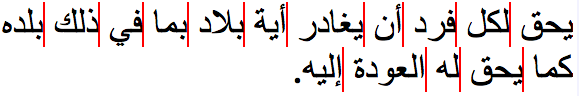

Many scripts work this way. Among others, they include scripts used for all major European languages, including Cyrillic and Greek; scripts used for major Indian languages, such as Devanagari, Gujarati, and Tamil; scripts used for modern Semitic languages, such as Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac; and scripts used for American languages, such as Cherokee and Unified Canadian Syllabic (UCAS).

Languages written in right-to-left scripts, such as Arabic or Hebrew or Dhivehi, also typically wrap full words to the next line. However they do so, of course, in the opposite direction from, say, English.

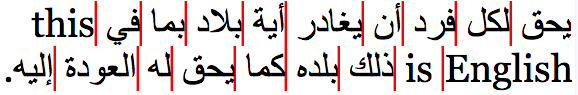

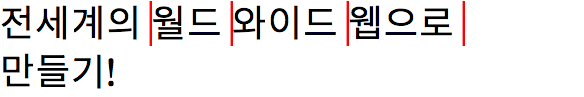

Text in languages such as Arabic, Hebrew or Dhivehi, however, gets significantly more complicated when it contains bidirectional text. If we make the text read '...في this is English ذلك... ' in the above example we end up with the following.

Looking at the above example, you will notice that the relative order of the English words has been rearranged across the line break. This is because horizontal bidirectional text is never read upwards, from line to line. This output is managed by the bidirectional reordering process, before line-break opportunities are calculated, and only affects the positioning of font glyphs. Characters in memory run in order of pronunciation, and don't change.

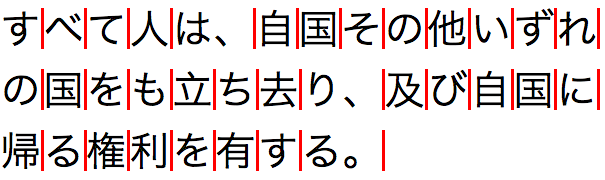

Vertically-set Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Traditional Mongolian wrap words upwards, but the new line appears to the left for CJK, and right for Mongolian.

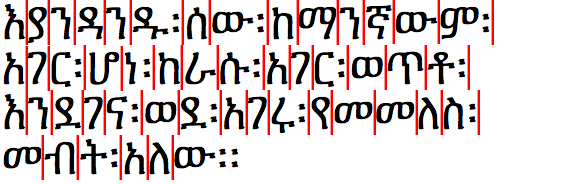

South-East Asia: no word separator

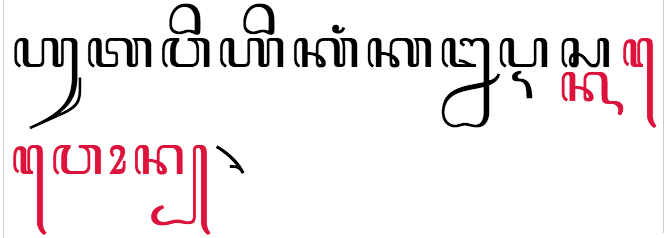

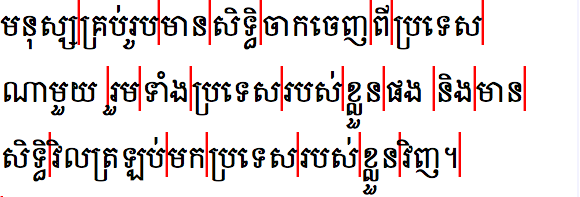

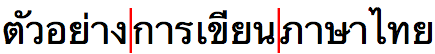

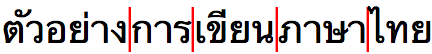

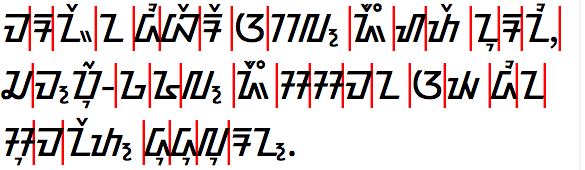

Thai, Lao, and Khmer are languages that are written with no spaces between words. Spaces do occur, but they serve as phrase delimiters, rather than word delimiters. However, when Thai, Lao, or Khmer text reaches the end of a line, the expectation is that text is wrapped a word at a time. For humans, this is is not too hard (if you speak the language), but applications have to find a way to understand the text in order to determine where the word boundaries are.

Most applications do this by using dictionary lookup. It’s not 100% perfect, and authors may need to adjust things from time to time. For example, here are two alternative sets of line-breaking opportunities for a Thai phrase.

The difference here is not just a question of faulty implementations. As mentioned earlier, the concept of what is a word in writing systems that don't clearly delimit them is somewhat fluid. The above differences arise from different subjective opinions about whether compound words should be wrapped whole or not to the next line.

In the past, the Unicode character U+200B ZERO WIDTH SPACE (ZWSP) was used to indicate word boundaries for these scripts, and some standard keyboards such as Khmer NIDA still generate ZWSP with the spacebar key, but recently major languages have line-breaking implementations at their disposal, which means ZWSP is not essential. Large-scale manual entry of ZWSP is also not very practical because the user cannot see the separator in most scenarios; this leads to problems with ZWSP being inserted in the wrong position, or multiple times. ZWSP may, however, be used to hand-craft and fix aspects of line-break behaviour.

It is also important to bear in mind that the scripts referred to here may be used to write languages other than those mentioned, in particular minority languages for which different dictionaries are needed. Since such dictionaries may not available in a given browser or other application, there is a tendency to use ZWSP in order to compensate.

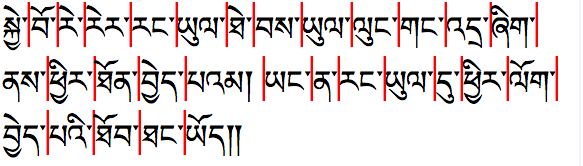

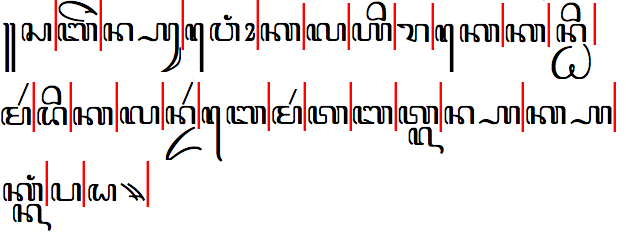

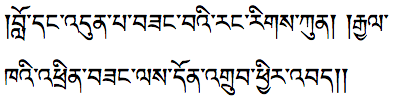

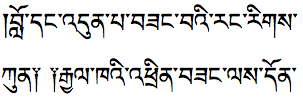

SHAD (pronounced shay)

SHAD (pronounced shay) RIN CHEN SPUNGS SHAD

RIN CHEN SPUNGS SHAD

le'u

le'u TALING

TALING