Punctuation

Overview

The role of punctuation and the scope of this chapter

The role of punctuation is functional and serves to segment text into smaller parts to benefit clarity of communication with the reader. Punctuation should be used consistently to assure that the meaning of the segments they produce is not changing across the document. The more subjective topic of how to use punctuation to break text into meaningful units is avoided here. Instead this section reviews and recommends how to use specific punctuation, in combination with other punctuation and formatting approaches, to affect visual clarity.

Punctuation in Relation to Surrounding Text

Punctuation and italics

Punctuation and boldface or color

Punctuation and font—aesthetic considerations

Parentheses and brackets in relation to surrounding text

Quotation marks in relation to surrounding text

Punctuation and space—one space or two?

Punctuation in Relation to Closing Quotation Marks

Periods and commas in relation to closing quotation marks

Other punctuation in relation to closing quotation marks

Colons and semicolons—unlike periods and commas—follow closing quotation marks; question marks and exclamation points follow closing quotation marks unless they belong within the quoted matter.

Single quotation marks next to double quotation marks

When single quotation marks are nested within double quotation marks, and two of the marks appear next to each other, a space between the two marks, though not strictly required, aids legibility. For print publications, typesetters may place a thin space or a hair space between the two marks (as in the print edition of this manual). In electronic environments (including manuscripts submitted for publication), a nonbreaking space can be used (as in the online edition of this manual); such a space will prevent the second mark from becoming stranded at the beginning of a new line.

Periods

Use of the period

In Ethiopic writing the period has a more limited use than in the west. In Ethiopic writing, the period, or "dot", is appropriate for denoting decimal values, forming an ellipsis, and in single word abbreviations (see XX, YY, ZZ).Periods in relation to parentheses and brackets

Periods in ellipses

Ethiopic Fullstop

Commas

Use of the comma

Commas in pairs

Commas relative to parentheses and brackets

Commas with “etc.” and “et al.”

Semicolons

Use of the semicolon

Colons

Use of the colon

Space after colon

Preface Colons

Use of the preface colon

Space after preface colon

Preface colons to introduce quotations or questions

Question Marks

Use of the question mark

The question mark in Ethiopian literature is used as it is internationally. Its primaray use is to indicate that the statement leading up to the mark is a direct question. It may also be used for a rhetorical question, to indicate doubt, disbelief, or a level of factual uncertainity of a statement.

An archaic question mark written with three vertical dots (፧) can be found in some legacy works. While the mark is recognized internationally as the "Ethiopic Question Mark" its use should be reserved strictly for the reproduction of materials that have employed it, and not as a substitute for the regular question mark in any new works.

Question marks in relation to surrounding text and punctuation

Question marks should be placed within any circumfix punctuation marks such as quotation marks, parenthesis and brackets. As a device for emphasis, a question mark may follow some other punctuation, specifically another question mark, an exclamation point, or an ellipsis. A question mark should replace, and not follow the Ethiopic wordspace.

With Space

Wrong: «እንዚህ እነማን ናቸው»?ብለው

Correct: «እንዚህ እነማን ናቸው?» ብለው

With Wordspace

Wrong: «እንዚህ፡እነማን፡ናቸው፡»?ብለው፡

Wrong: «እንዚህ፡እነማን፡ናቸው፡?»ብለው፡

Correct: «እንዚህ፡እነማን፡ናቸው?» ብለው፡

Exclamation Points

Use of the exclamation point

Exclamation points in relation to surrounding punctuation

Use of the inverted exclamation point

Hyphens and Dashes

Hyphens in compound words

Hyphens as separators

En Dashes

Em Dashes

- 2-em dash

- 3-em dash

As a minus sign

With line breaks

With an unfinished number range

In lists, indexes, and tables

Parentheses

Use of parentheses

Parentheses for glosses or translations

Parentheses within parentheses

Parentheses with other punctuation

Brackets and Braces

Use of square brackets

Square brackets in translated text

Square brackets for parentheses within parentheses

Square brackets with other punctuation

Angle brackets and braces

Slashes

Slashes to signify alternatives

Slashes with dates

Slashes in abbreviations

Slashes as fraction bars

Slashes and line breaks

Speech Quotation

Guillemets pointing outwards («like this») are the preferred marks to indicated speech. Double quotes, in directional “smart” styling, may be used when guillemets are not available to a writer, but should otherwise be avoided. Favoring guillemets over quotation marks is both in keeping with pre-digital publishing and avoids confusion with the role of apostrophe (see ).

Quotation marks relative to other punctuation and text

In keeping with parentheses and brackets (), guillemets marks should appear in the same font style, regular or italic, as the surrounding text and not the style of the text enclosed.

Inner quotation marks

Inner quotation should be indicated with single guillemets (‹ and ›).

Apostrophes

Use of the apostrophe

Apostrophe (’) is an important symbol to modern Tigrinya that is applied between words in a contraction. If the second word begins with a vowel, it will be dropped. Apostrophe is then thought of as taking the place of a silent vowel. No other use of apostrophe in the Ethiopic context is known.

“Smart” apostrophes

In published works the directional “smart” (or “curly”) apostrophe should be used. This apostrophe appears like a raised western comma and should be in the same typeface weight as the letters that will surround it in a contraction.

Spaces

Use of the space

Both the Ethiopic and Western (unprinted) word spaces are important in Ethiopic writing and an author may chose to use either space as the document space.

Like the western space, Ethiopic wordspace is not punctuation per se, but plays a similar if more fundamental role. Both are used as a separator between words, however special rules apply when the Ethiopic wordspace would precede or follow punctuation and numerals. These special rules will be reviewed in the following subsections.

Spaces with punctuation

Consider space after a terminating punctuation ( ! ? ። ) in Modern Classic style.| May Precede | May Follow | |

| ፣ ፥ ፤ ። . … ! ? | No | No |

| @ $ % + - = | No | No |

| ‹ « “ ‘ ( [ { | Yes? (Historic -Yes) | No |

| } ] ) ’ ” » › | Yes | Yes? (Historic -No) |

Spaces with dates

Spaces with measurements

Multiple Punctuation Marks

Likely combinations for multiple punctuation marks

Abbreviation-ending periods with other punctuation

Periods with question marks or exclamation points

Commas with question marks or exclamation points

Question mark with exclamation point

Lists and Outline Style

Lists and outlines—general principles

Lists with item markers are a common practice found in modern Ethiopic writing. Lists may be ordered where the sequence is important and applies a “counter” that is numerical using either Ethiopic or Arabic numerals, or alphabetical applying the Ethiopic syllabary in keeping with the language of the document. Unordered lists are also used applying basic geometrical shapes such as circles and squares, solid or hollow, or more decorative shapes at the author’s discretion. Lists may be formatted vertically, vertically and multi-level, or inline (AKA “run-in”) and single level.

Style guides provide recommendations for the logical grouping of items within a list and for forming the phrases of the listed items and detail rules for their internal punctuation. In this section we focus only on formatting and positioning rules that computer software would automate for an author. List discussed here are lists that occur in text and does not apply to table of contents, lists of illustrations, lists of tables, glossaries or indexes. These more specific kinds of lists are discussed in other sections.

Run-in versus vertical lists

Two list layout orientations can be used. A list maybe laid out vertically, in a new paragraph with one list item per line. A list may also be presented horizontally within a sentence (known as “run-in” or “inline” lists). Run-in lists are more appropriate when the listed items are relatively short and the list forms a sentence with the introductory text (see ). List where the items may be longer phrases or full sentences, or have multiple levels, should be set vertically (see ).

Run-in lists

When letters or Ethiopic numerals are used to mark the items in a run-in list they should be followed by a slash, “/”. If western numbers are used to form a list, a dot “.” maybe used in place of slash. If the introductory material forms a grammatically complete sentence, a preface colon, “፦”, should precede the first listed item.

(needs review) Listed items should be separated by a comma, “፣”, unless item text also requires a comma, then semicolon, “፤”, should be used instead.

TBD: Review for enclosing parenthesis use and enclosing double slash like /ሀ/

Vertical lists punctuation, and format

A vertical list is best introduced by a grammatically complete sentence, followed by a preface colon, “፦”. The list that follows may then be either ordered or unordered as introduced in Section . If the list is unordered no end punctuation is needed unless the content forms a complete sentence.

Vertical lists punctuated as a sentence

When vertical list items complete the sentence of the introductory text, commas or semicolons may be used between the items, and a period should follow the final item. Optionally, the introductory paragraph may continue inline following the final list item as depicted in :

ለ/ ጾመ ድጓ፣

ሐ/ ዝማሬ፤

መ/ መዋሥዕት፣

ሠ/ ምዕራፍ የተሰኙት ናቸው። ለልዑል እግዚአብሔር ክብርና ምሥጋናይግባውና ስለ ፬ቱ ጸዋትወ ዜማዎች

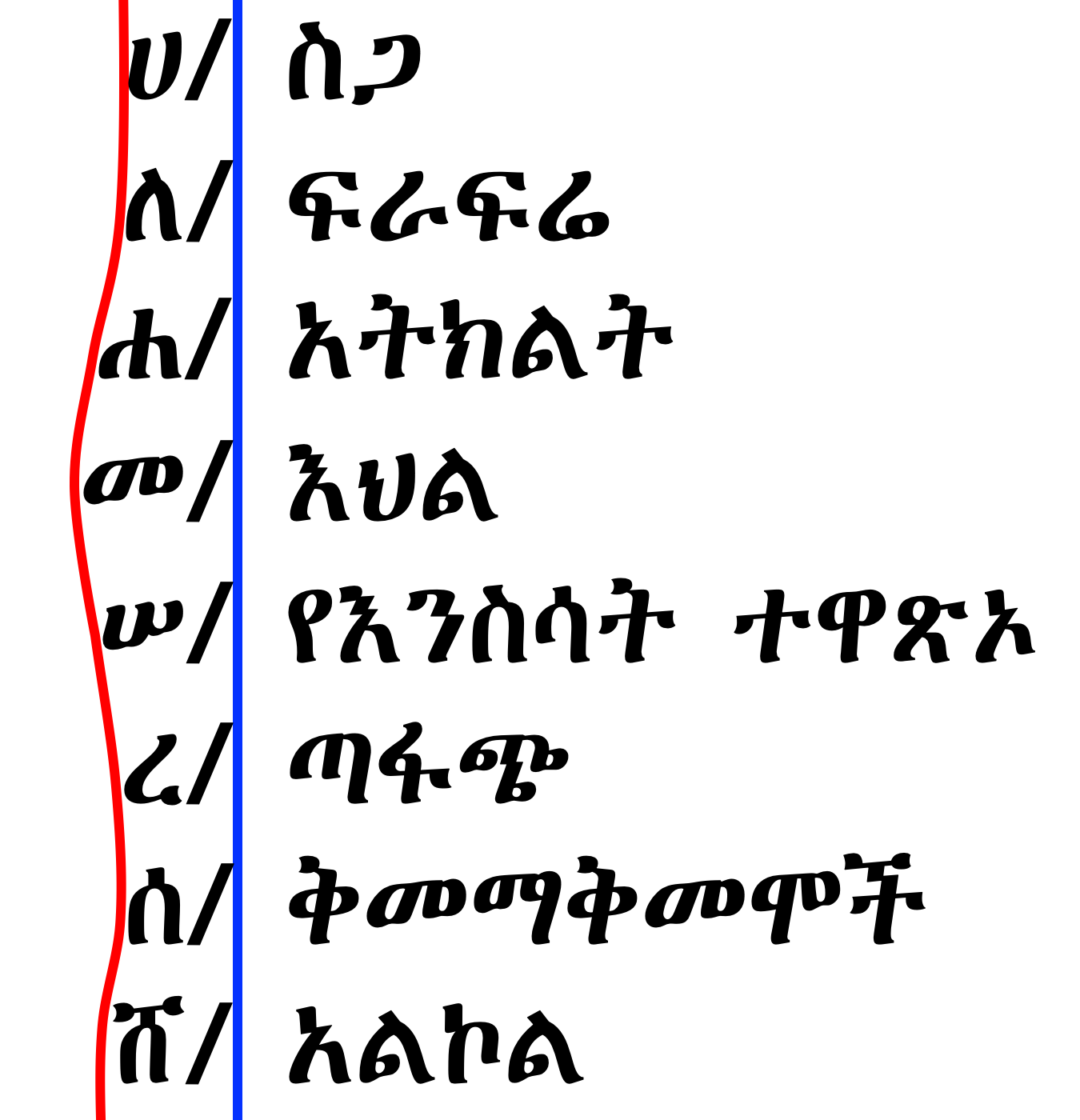

Vertical lists with multiple levels (outlines)

Where items in an ordered list introduce an additional list, both numerals and letters may be used. In keeping with the main list, any run over lines from the inner list items should be aligned with the first word following the item marker.

TBD: discuss change in list item counter, and list item marker at inner levels

- ሀ/ ስጋ

- ፩/ በግ

- ፪/ ብሬ

- ፫/ ዓሣ

- ፬/ ዶሮ

- ለ/ ፍራፍሬ

- ፩/ ሙዝ

- ፪/ አናናስ

- ፫/ ብርቱካን

- ፬/ ወይን

- ሐ/ አትክልት

- ፩/ ቲማቲም

- ፪/ ጎመን

- ፫/ ሽንኩርት

- ፬/ ድንች

- መ/ እህል

- ፩/ ጤፍ

- ፪/ ስንዴ

- ፫/ ገብስ

- ፬/ ሩዝ

Ordered list counter suffix

The list “counter” is the number or letter that begins a list entry (e.g. “3”, “፫” or “ሐ”). The “list counter suffix” (also called the “list item marker”) is the symbol that follows, or in some case surrounds, the counter. For example: “.”, “/” or “()” in “3.”, “፫/” and “(ሐ)”.

The recommended counter suffix for Ethiopic text in any language is the slash “/” symbol. Slash is recommended as the default suffix while authors are allowed to easily switch to a common alternative such as “፦”, “.”, “)” and “፡”.

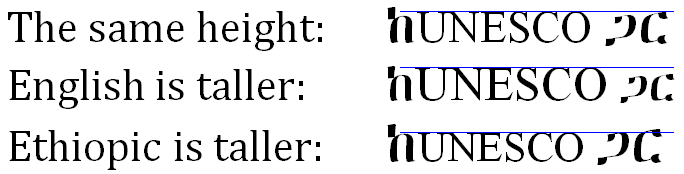

List counter suffix alignment

In vertical lists, the list item text should initiate at the same horizontal position from the left margin. It is recommended that this positioning be achieved by aligning the list counter suffixes. The resulting list should appear as if the list were laid out in a table where the counter and its suffix appear right-justified in the first column, and the list text appearing left justified in the second column. depicts suffix based list alignment.