gpc

Global Privacy Control (GPC) Legal and Implementation Considerations Guide

Editors: Aram Zucker-Scharff Justin Brookman Sebastian Zimmeck

0. tl;dr

Global Privacy Control (GPC) is a proposed specification designed to allow Internet users to notify businesses of their preference to not have their personal information sold or shared, or used for cross-context targeted advertising. It consists of a setting or extension in the user’s browser that provides a mechanism that websites can use to indicate they support the specification.

This Legal and Implementation Considerations Guide is designed to give an overview of how GPC operates as well as a summary of the legal effects GPC may have in different jurisdictions. However, this document is for reference purposes only — it does not constitute legal advice.

- Global Privacy Control (GPC) Legal and Implementation Considerations Guide

1. Draft Specification

You can find the draft specification here.

2. Background

An increasing number of laws and regulatory environments require that sites respect people’s choices to not be tracked across different contexts. While these laws describe privacy choices in different ways it is clear that they represent an interest in giving people the capability to exercise a right to privacy and that people have an interest in exercising that right.

Some laws establish a requirement for a universal control that can present this opt out request at a user-agent level automatically, making it easier for people to exercise their rights without negotiating a site-level user interface.

With this in mind the GPC specification proposes a way for user-agents to present people’s preferences to opt out to sites via both a header and a JavaScript object. The specification intends to capture the standard ways sites currently handle opt out choices.

The motivation of GPC is to:

- Make it easy for people to clearly and unambiguously present their privacy preference to a website and the various technologies it may run.

- Allow website developers to incorporate people’s privacy choices with as little delay and complexity as possible.

The specification also provides an option for sites to provide a GPC Support Resource that allows sites to state that they are aware of and support the GPC specification. Some laws or regulatory environments may require GPC compliance. The goal of the GPC Support Resource is to allow sites to assert their support actively. This demonstration is useful to regulators, lawyers, and activists in determining the impact of people’s privacy choices as well as sites’ awareness. It is also useful in giving people a clear signal that their privacy choices are respected to the best of a site’s ability.

3. Solution

The GPC signal is either on or not present. If it is on, then an individual is expressing a privacy choice, for example, to opt out of the sale and data sharing per the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Sites may choose to support this request beyond what they are legally required to do and their vendors may choose to do so as well.

If someone expresses a preference for their information to not be sold or shared, a device or browser that supports the feature will enable GPC signals. GPC is signaled with an HTTP header and a property that can be read by JavaScript. Sites can read either signal.

3.1 Header

When GPC is enabled, a browser includes the following header field in all requests that it makes:

This signal will be absent when no preference has been expressed or where GPC has been disabled.

3.2 Navigator Object

Browsers that support JavaScript will expose navigator.globalPrivacyControl. If navigator.globalPrivacyControl is true, then GPC has been enabled.

The navigator.globalPrivacyControl attribute will be present and have a value of false if the browser supports GPC but there has either been no preference expressed or GPC has been disabled. This attribute will be absent only if the browser does not support GPC.

3.3 Signal Semantics

When GPC is enabled, the browser is expressing a do-not-sell-or-share preference. These signals are direct requests to sites to respect that preference.

The specification presents this design to ensure that there can be no mistake in understanding the intent or state of the signal. If the signal is active, it expresses an individual’s privacy choice.

3.4 GPC Support Resource

The GPC Support Resource should be at https://{yourwebsite.com}/.well-known/gpc.json. The GPC Support Resource should only be hosted by domains that are concerned with listening to the signal. If you develop technology to emit the signal, it is not intended that the GPC Support Resource is stating something about your technology.

A website that is intending to listen to and take action based on the GPC signal in any way should have the following style object in that JSON file:

{ "gpc": true, "lastUpdate": "1997-03-10" }

The lastUpdate value is meant to reflect your understanding of the specification. If the specification changes in such a way as to not be backwards compatible, this value gives adopters the capacity to note their understanding of the signal being based on the state of the GPC specification at the particular time they last updated the file.

Sites may respect GPC without the GPC Support Resource. Sites that do not respect GPC may do so either by setting gpc to false or not providing the GPC Support Resource. User-agents may parse the GPC Support Resource and announce its presence, lack of presence, or values to people in a way that indicates their understanding of the domain’s support for GPC. Not all legal regimes may consider sites able to reject the GPC signal. Consult your lawyer if you intend to reject the GPC signal.

4. Legal Effects

Where laws arise to provide Internet privacy GPC intends to have a very specific privacy purpose. It asks domains not to share or sell people’s personal data, or to use personal data across different contexts, using similar definitions to CCPA and other U.S. state privacy laws. Other nationalities or regions may choose to incorporate the signal directly or may find user-agents using it. While the legal or regulatory requirements to respect GPC vary, people’s intent in exactly what they are requesting should be considered consistently.

GPC is not necessarily intended to invoke every new privacy right in every jurisdiction. For example, GPC is not intended to globally invoke data deletion rights on every website people visit. GPC is also not intended to limit a first party’s use of personal information within the first-party context (such as a publisher targeting ads to an individual on its website based on that individual’s previous activity on that same site). For that reason, GPC should not be interpreted as exercising the CCPA’s right to limit the use of sensitive information in a first-party context.

4.1 GPC in the US

Since 2018, at least nineteen states have passed comprehensive state privacy laws that include, among other rights, the right to opt out of the sale or sharing of personal information and/or the right to opt out of cross-context targeted advertising. Many of these laws explicitly state that consumers may exercise these rights through a universal signal, including a signal sent through a browser or operating system. At least four states have declared that receipt of a Global Privacy Control signal is to be interpreted as a legally binding exercise of the opt-out right in that state.

4.1.1 The California Consumer Privacy Act

In 2018, California passed the first comprehensive privacy law in the United States. In addition to transparency obligations, the right to access personal information, and the right to delete personal information held by businesses, the CCPA gave California residents for the first time the legal right to opt out of the sale of their personal information. The CCPA included text that a consumer could appoint another entity to exercise their rights on their behalf. In January 2021, the California Attorney General issued guidance to businesses that sending GPC signals is to be interpreted as a legally binding exercise of opt-out rights under California law. Subsequently, the California Attorney General’s office updated its Frequently Asked Questions page, which in addition to other guidance, stated that GPC signals were legally binding invocation of opt-out rights under California law.

Under the CCPA, the California Attorney General is empowered to issue regulations offering more clarity about specific portions of the text of the law. The initial set of regulations provided more clarity on how global opt-out signals should be interpreted as opt-out requests under the law. See § 999.315. Requests to Opt-Out (though note that these regulations have since been superceded — see following paragraphs).

In November 2020, California voters approved an update to the CCPA under the California Privacy Rights Act ballot initiative. The initiative expanded the CCPA in a number of ways, including through the creation of a new privacy regulator (the California Privacy Protection Agency) and through increased specificity on the legally binding nature of global privacy signals. Under the CPRA, the California Privacy Protection Agency was directed to expand on previously issued regulations.

In March 2023, the Agency issued revised regulations, including provisions on the operation of “opt-out preference signals.” See § 7025. Opt-out Preference Signals. The text includes detailed requirements around issues such as: the technical requirements for opt-out preference signals, when to apply browser-based opt-out preference signals to other consumer data, and when businesses can rely upon specific consent to disregard opt-out preference signals. The regulations includes illustrative examples on how the rules should work in practice.

In August 2022, the California Attorney issued its first enforcement action under the CCPA, alleging that the makeup company Sephora adopted an unduly narrow definition of “sale” under the CCPA and failed to respond to GPC requests as legally valid opt-out requests. The company was required to pay a fine of $1.2 million and agree to substantial injunctive relief, including agreeing to treat GPC signals as requests to opt out of the sale of personal information.

4.1.2 The Colorado Privacy Act

In July 2021, Colorado enacted the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), which offered similar — though slightly different — protections as the California Consumer Privacy Act. One difference is that the CPA offers two different though related opt-out rights — the right to opt out of data sales and the right to opt out of cross-context targeted advertising.

The text of the CPA explicitly provides for global privacy signals, stating “a consumer may authorize another person, acting on the consumer’s behalf, to opt out of the processing of the consumer’s personal data . . . including through a technology indicating the consumer’s intent to opt out such as a web link indicating a preference or browser setting, browser extension, or global device setting.” See § 6-1-1306(a)(ii). The CPA then included a number of additional requirements of global privacy signals, including: the signal should not be sent by default but should reflect the user’s affirmative choice, it should be as consistent as possible with similar mechanisms in other states, and the user agent sending the signal should not “unfairly disadvantage” another data controller.

The Colorado Privacy Act also directed the Colorado Attorney General to issue more detailed regulations, including specifically on the operation of global privacy signals. On March 2023, the Colorado Attorney General’s office published the initial regulations implementing the privacy law, including greater specificity on the operation of universal opt-out mechanisms (see Part 5, Universal Opt-Out Mechanism). These regulations provide clarity on a number of issues, including restrictions on data use by companies receiving the signal. The regulations also clarify the rules on default settings, stating that general purpose, pre-installed browsers may not set universal opt-out signals by default, but if a product is marketed as exercising users’ privacy choices, it may send an opt-out signal to controllers without additional consent from the user.

The regulations also set up a “registry” of legally binding signals under the law to provide greater clarity to businesses as to which universal opt-out mechanisms must be treated as binding opt-out requests. In October 2023, the Colorado Attorney General’s office issued a call for proposals for signals that should be included in its registry. In February 2024, the office published the first official registry of legally binding universal opt-out mechanisms. The only signal recognized as legally binding was the Global Privacy Control.

4.1.3 Other states that explicitly provide for universal opt-out mechanisms

In addition to California and Colorado, at least ten other states have passed comprehensive privacy legislation that explicitly provides for the operation of global privacy signals that must be treated as legally binding opt-outs under the law. Most of these state laws are broadly similar to the text of the Colorado Privacy Act, in that they apply to both sales and cross-context targeted advertising, and have similar provisions requiring, for example, that the signals reflect the intent of the user and that they not unfairly disadvantage other controllers.

However, they also differ in a number of key ways. As one example, states like Texas and Nebraska provide that specific global opt-out signals will be deemed valid if they are legally recognized in another state jurisdiction. Most of these states do not provide for rulemaking from the Attorney General to issue more clarity on the operation of the global opt-out provisions, though regulators may offer more informal guidance through FAQs (as California originally did) or may bring enforcement actions to clarify the boundaries of the law.

Two states — Connecticut and New Jersey — have issued FAQs explicitly stating that GPC should be treated as a universal opt-out under their laws.

4.1.4 States that have privacy law that is silent on universal opt-out mechanisms

Some U.S. states have passed comprehensive privacy laws that make no mention of universal opt-out mechanisms. It is not clear what legal effect — if any — global mechanisms like GPC would have in such states. Because those state laws give significant discretion to companies in how opt-out rights are offered to consumers, it may well be the case that universal opt-out signals would have no effect under those laws. However, the ultimate interpretation of those laws lies with local enforcement agencies and the courts.

4.1.5 Federal law and states without dedicated privacy laws

The majority of U.S. states have not enacted comprehensive privacy legislation, and federally there is no privacy statute specifically covering commercial information. The Federal Trade Commission and state Attorneys General have enforced general purpose consumer protection law that prohibits unfair or deceptive practices against certain privacy behaviors, though none have made a specific claim about how GPC intersects with those laws. The FTC has proposed to issue regulations under its consumer protection statute governing “surveillance capitalism,” and some privacy advocacy groups have argued that failure to respond to universal opt-out requests could be treated as an unfair business practice under such a regulation.

4.2 GPC outside the US

The European Union and European Economic Area have the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This law provides for a number of bases for data processing, including consent and the “legitimate interest” of the data controller. For processing pursuant to a company’s “legitimate interest,” Article 21 of the GDPR offers people an ability to object, or opt out, of such processing. As GPC is intended to convey a general request that data controllers limit the sale or sharing of the person’s personal data to other data controllers, European regulators may deem GPC to constitute a legally binding invocation of Article 21 rights. To date, no European regulator has explicitly made this case, though some commentators have argued that GPC has legal effect under the GDPR.

Mauritius, an African country, has the Data Protection Act (DPA). The DPA was inspired by the GDPR. The law provides for a number of bases for data processing, including consent and the “legitimate interest” of the data controller. For processing pursuant to a company’s “legitimate interest,” Article 24 of the DPA offers people an ability to opt out of such processing. As GPC is intended to convey a general request that data controllers limit the sale or sharing of the person’s personal data to other data controllers, Mauritian regulators may deem GPC to constitute a legally binding invocation of Article 24 rights. That would be the case if people’s GPC opt out preferences are their only known opt out preferences or their GPC opt out preferences are in line with any other opt out preferences they invoked. However, in case of conflicts there might be ambiguities as there is no explicit mention of global opt-out mechanism winning over a direct consent to a specific sharing request on a specific site.

The Privacy Commissioner of Bermuda has also written that GPC may ultimately be interpreted to exercise legal rights under its Personal Information and Privacy Act.

5. User Experience Considerations and Recommendations

It is not considered standard for W3C specifications to present user interface recommendations or restrictions. User interfaces are the domain of user-agents who, being closest to the user, best understand how their users interpret and react to the underlying functionality. For GPC, some user-agents may present themselves as privacy-focused technology, in which case it may make sense for the signal to be defaulted to on, which, for example, is supported in California and Colorado for privacy-focused technology. Some user-agents may be generic, with no expectation for people setting defaults. Some user-agents may present GPC in different formats and devices and necessitate unique user interface requirements.

This Guide presents examples of user-agent user interfaces for GPC as an aid to adopters who are interested in or required to implement GPC as to how it can be presented.

5.1 Example Presentations of User-agent Level UI

The following examples come from the OptMeowt browser extension, which is developed at the privacy-tech-lab at Wesleyan University. We also show how Mozilla surfaces the GPC setting in Firefox. These examples are shown to illustrate. They are not meant as a comprehensive set of UIs for GPC.

Whichever user interface applications are implemented, they are expected to meet accessibility standards.

User interfaces are further expected to have a clear visible switch for turning on the GPC signal that can clearly distinguish between active and inactive. For GPC “active” always means an individual is exercising their choice to opt out of sharing and cross-site usage to the extent provided by the law.

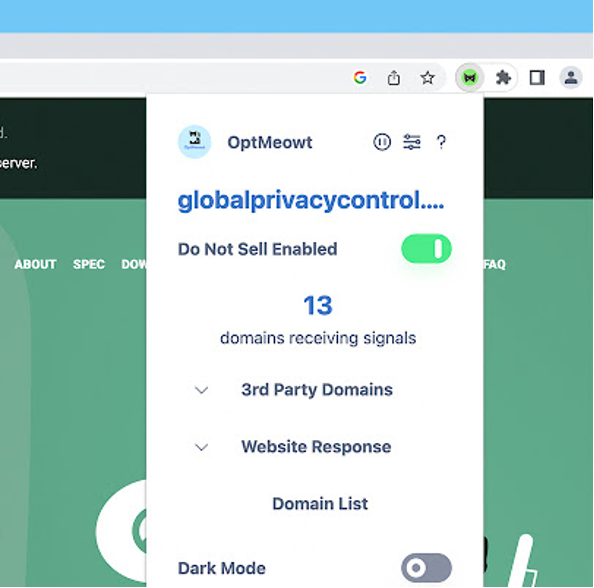

The OptMeowt popup showing GPC details of the current site.

The OptMeowt popup showing GPC details of the current site.

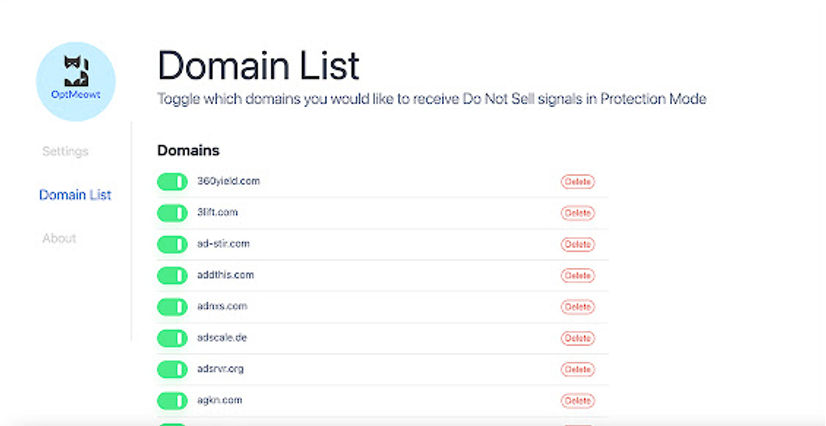

User-agents may choose to allow people to manage the GPC signal for individual domains. The Individual domains can be represented to the user as a list that clearly indicates their settings. In such a list people may be able to add individual domains, domains may be automatically added, and people may manage domains on which they have already made an active choice, or exclude domains from the GPC opt out signal being active. When people choose a GPC setting for a site, it is expected that the user-agent retain that setting until they make an active choice to change it.

The OptMeowt domain list for setting GPC on individual sites.

The OptMeowt domain list for setting GPC on individual sites.

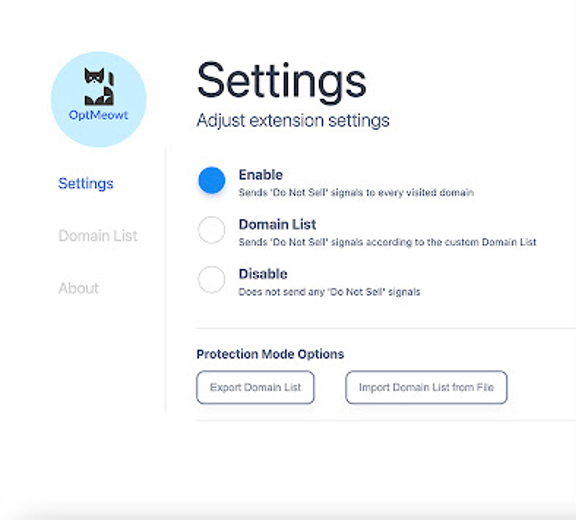

It is expected that most people will choose if they want to universally activate GPC across all domains and requests. Interfaces should reflect GPC’s intent to be as straightforward and simple as possible. People may also choose to disable GPC universally for their user-agent.

The universal GPC setting of OptMeowt.

The universal GPC setting of OptMeowt.

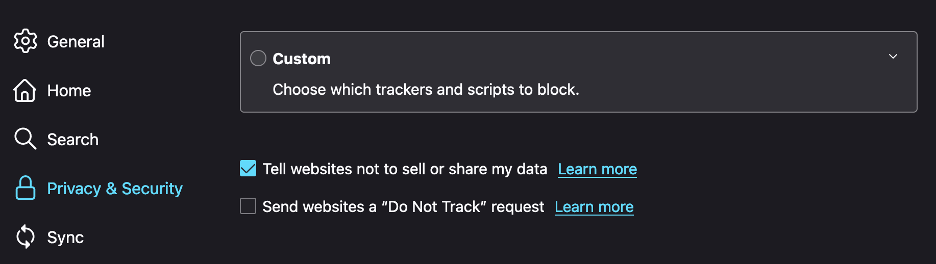

The universal setting of GPC in the Firefox browser settings.

The universal setting of GPC in the Firefox browser settings.

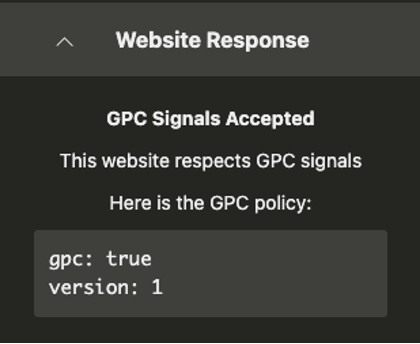

A user interface can show what response is at https://{yourwebsite.com}/.well-known/gpc.json and display that information to the users so they can understand what claims the website is making in terms of GPC compliance. This can be done regardless of the properties included on the JSON document, the main concern is the value of the gpc property, as seen here.

An example of how GPC responses can be surfaced (OptMeowt).

An example of how GPC responses can be surfaced (OptMeowt).

5.2 User-agents

The above examples are from an extension in a web browser. User-agents should implement similar interface conventions. The authors of this document recommend that user-gents have some way to display to people the state of their GPC signal when it is on during the course of regular interaction with the site instead of putting it behind a settings page.

A setting should be included to manage GPC. At the very least a simple Boolean-value switch should be available to the user within settings to manage GPC universally for the user-agent.

If GPC is not turned on by default, there should be a control that is accessible to people to turn it on when interacting with an individual site.

If the user-agent makes the GPC setting visible when active, it should retain individuals’ privacy choices when they turn off GPC for a specific site.

User-agents should not challenge people with a request to set GPC in either mode beyond initial setup. Per-domain settings of GPC should be up to an individual to engage with, not pushed via a notification, modal, pop-up, or similar interactive element.

Many user-agents offer a “private browsing” or “incognito” mode that provides heightened privacy protections when in use, such as not retaining local history or cookies at the end of a session. Depending upon how that private mode is described to users, the developers of the user-agent may deem it appropriate to send GPC to websites while this mode is activated as a means of offering additional privacy protection. While browser developers make decide that additional consent or user prompting is unnecessary before sending GPC in such cases, they should be transparent about the fact that in “private” or “incognito” mode, GPC will be sent.

5.3 Adopting on Your Website

Given the complexities of existing privacy choice and consent frameworks, sites that implement GPC should disclose how they treat it in any jurisdiction for which they adopt it and how they deal with conflicts between a GPC signal and other specific privacy choices that an individual has already made directly with the site, including instances where third party sharing may be permitted, such as sharing to service providers/processors or at the direction of the individual.

Where industry standards set specific strings or signals that are needed to communicate people’s privacy choices, sites should anticipate translating GPC into the downstream signal. A good example of such setting is handling GPC to set California-based US Privacy Strings for advertising technology:

if (

navigator.globalPrivacyControl &&

identityObject.geoState === 'CA'

) {

this.uspapi.uspStringSet = true;

this.uspapi.setUSPString(`1YYY`);

} else if

Setting the USPAPI for propagating GPC downstream.

Generally website developers should consider GPC signals to be identical to a user flipping the opt out switch on their website and take action accordingly.

5.4 Consent to Disregard a Universal GPC Signal

A do-not-sell-or-share preference is when a person generally requests of all website publishers that their data “not be sold or shared.” However, it is possible that a particular publisher would seek to enter into a separate agreement with a user permitting that publisher to sell or share the user’s data notwithstanding the general preference. The GPC spec does not provide for a mechanism or syntax to negotiate or indicate such an exception, so any user consent to tracking would be communicated apart from the GPC signal.

When and how a separate agreement to disregard GPC requests overrides the legal status of the signal will be a matter of local law. Some jurisdictions that have explicitly endorsed GPC as a legally binding opt-out signal have also placed limitations on how companies can request permission to track despite the general signal. One rationale for such limitations is that without some restrictions, users with GPC enabled could be inundated with countless requests for exceptions to track as they browse the internet — undermining the fundamental purpose of offering a simple, binary universal opt-out tool. Both California and Colorado, for example, constrain how overrides for universal opt-out signals like GPC can be requested, including rules against retaliating against users for exercising privacy rights, conditions for valid consent, and limiting how frequently companies can ask consumers to reconsider opt-out requests.

6. Alternatives Considered

The authors of GPC considered other options for how the signal would work. The current state of privacy controls across the world is varied. The authors have experience both working on and implementing these more complex controls and found that people generally consider them to be unnecessarily complex. If people intend to make privacy choices, they almost always intend to exercise their rights broadly, e.g., opting out from all sites they visit, no matter how many individual controls exist. More recent laws have also adopted this understanding and moved towards requiring universal or significantly fewer degrees of control. GPC reflects this understanding of people’s privacy choices and, therefore, works in support of these laws.

The signal has been through a few iterations with the specification before it was submitted to the W3C. More complex signals, more extensive data, and different delivery formats were all considered. Additional complexity in the signal creates fingerprinting risk. Delivering the signal for JavaScript-based consumers via a promise was considered as a more privacy-preserving option that would allow greater complexity but was rejected to prefer performance and simplicity.

Removal of the GPC Support Resource was considered as well as further simplification of the contents. However, the maintenance of both the GPC Support Resource as an indicator of compliance and the presentation of the date were both reinforced during consultation with lawyers as extremely useful for maintaining documented compliance and dealing with potential legal activity, especially in cases of specification updates.