MathML is used by VoiceOver, Orca, JAWS, and NVDA to provide accessible math on the web. A large majority of math on the web is now accessible thanks to MathJaX and the tricks it uses to render the math visibly in all browsers but to hide the “span soup” it uses for display yet still expose MathML to AT. The MathML WG is working on defining MathML Core to solve the issues with displaying MathML on the web. This document focuses on ways to improve the accessibility of MathML in cases where the presentation of the mathematical expression is ambiguous; notational ambiguity is discussed below.

Since its beginnings in 1998, MathML has had two parts: Presentation MathML which describes the arrangement of math symbols, and Content MathML describes the composition of math operators. These two subsets of MathML carry complementary information and can be used separately, or combined using Parallel Markup (described below). Neither of these forms carries adequate information to provide unambiguous accessible output. While some mathematical concepts are explicit or can be inferred, the general problem of understanding mathematical notation is too hard for present-day systems. For the hard cases, annotations need to be provided by an author. This document examines two central questions:

This document makes no conclusions. It lists some of the strengths and weaknesses of the approaches presented. The reader is invited to comment on those approaches and/or provide alternatives as the WG wants to come to a solution that works within the web platform to address the problems noted below.

The goal is to allow authors/authoring tools the ability to capture, in MathML, enough information so that an expression can be correctly rendered by screen reader applications. It is likely that further applications such as search, computation, and conversion to other formats may benefit from the same annotations, but the focus of this document is on enhancing accessibility.

The Working Group is committed to backwards compatibility. Any solution to these problems should not invalidate old documents, but should allow progressive enhancement of existing content. Moreover, to allow flexible and progressive adoption, authors should be able to enhance the math contained in their documents as little or as much as they choose.

In the following sections, this document discusses the current state of Web math APIs, how AT renders math, and the problems that ambiguous math presents to AT/users. It explores some ideas based on ARIA and CSS, and parallel MathML markup. It also presents a new potential extension for presentation MathML.

Mathematical expressions leverage text, graphical symbols, grids and symbol decorations. Sources of extra difficulty come from having multiple ways to read the same mathematical expression and also because the words used in speech are distinct from braille codes for mathematics that are based on the graphical notations, not the words.

AT usually gets information about a web page through accessibility APIs provided by an OS. The information used is built by the browser from the browser’s DOM and is represented in a parallel structure called the Accessibility Tree. In general, the accessibility tree is a simplified version of the DOM in that only information needed by AT is exposed. For example, a span with no semantic information will not be part of the accessibility tree. A more detailed description can be found in MathML Accessibility API Mappings 1.0 [early stage working draft, 2021].

The platform APIs in general have not provided much support for mathematical notation beyond a generic “math” role. However, ATK (used by Orca) added a few roles to support math in 2015; that support is not sufficient to represent a number of mathematical notations (e.g., “munder” and “msubsup”). Apple has tentatively(?) added MathML equivalent roles to AX API (based on what is listed in the MathML API Mappings), but those (sub)roles are not documented anywhere on Apple’s website. The current state appears to be:

MathML and SVG live in somewhat parallel worlds in their relationship to HTML. SVG Accessibility API Mappings (working draft, May 2018) gives details on SVG accessibility. In general, the document recommends adding ARIA to enhance the accessibility of SVG. Specifically, it states that shape elements (circle, etc) among many others do not go into the accessibility tree unless given semantics via ARIA (e.g, by aria-label). Also, more germane to MathML, elements that do not render visually should never be in the accessibility tree. For MathML, these invisible elements include the non-presentational part of semantics, maction, etc. Unlike math, there is no specialized braille language for graphics, nor is there an expected way SVG objects should be spoken in the absence of ARIA enhancements.

Ideally, platform APIs should allow those tags and attributes of MathML that are informative in narration to be exposed in a straightforward manner. We also refer to such pieces as ones of “semantic value”. Most MathML tags indeed participate; some attributes do also. Examples of attributes that have semantic value are the “mathvariant” attribute of token elements, as well as the “linethickness” attribute of mfrac. To illustrate, a common binomial coefficient notation uses a “linethickness” of zero, while the same MathML expression with a positive “linethickness” can be a fraction or the Kronecker symbol.

For years, the accessibility of mathematics in print, and later on the web and in other formats, has been a large pain point to both those who produce accessible content and to those who consume it. Typically, inaccessible images were used. Even when alternative text was provided, the text could not be converted to braille or navigated in a useful manner; only word-by-word navigation was possible.

The use of MathML has dramatically reduced these problems. In addition to speech, using MathML allows the specialized braille formats used for mathematics to be generated. Unlike text, these formats are not based on the words used to speak the expressions, but on (mostly) the notations used to represent them. Critically, MathML allows readers to explore the mathematical structure of an expression when it is too complicated to be understood when read from start to end.

A remaining problem with the accessibility of MathML occurs because mathematical notations can be ambiguous. For example,

While all AT speaks

Higher mathematics adds an additional tier of complexty. In it, even

Some notations, such as fractions and square roots, may require bracketing words or tones to indicate the start and end of an expression, for readers who can’t see the presentation. For example,

To fully appreciate the difference between presentational and semantic speech, below is a question from a MathCounts middle school math competition.

“Given the congruent right triangles A B C and A superscript prime B superscript prime C superscript prime [pause] A equals open paren 0 comma 5 close paren [pause] B equals open paren 12 comma 0 close paren [pause] C equals open paren 0 comma 0 close paren [pause] A superscript prime equals open paren 3 comma 4 close paren [pause] C superscript prime equals open paren 0 comma 0 close paren [pause] and X is the intersection of modifying-above A superscript prime B superscript prime with bar and the x axis [sentence pause] What is the area enclosed by triangle X B superscript prime C superscript prime divided by the area of A superscript prime B superscript prime C superscript prime ? [sentence pause] The area enclosed by A superscript prime B superscript prime C superscript prime is the same as that of A B C, which is 12 times 5 divided by 2 equals 30 units sup 2 [sentence pause] The slope of C superscript prime A superscript prime is 4 divided by 3 [pause] so the slope of perpendicular C superscript prime B superscript prime is the negative reciprocal [pause] or minus 3 divided by 4 [sentence pause] The length of modifying-above C superscript prime B superscript prime with bar is the same as the length of C B [pause] namely 12 units [sentence pause] Therefore [pause] the coordinates of B superscript prime are B superscript prime sub x equals 0 plus start-fraction 4 over square-root of 3 sup 2 plus 4 sup 2 end-square-root end-fraction times 12 equals plus 9.6 and B superscript prime sub y equals 0 minus start-fraction 3 over square-root of 3 sup 2 plus 4 sup 2 end square-root end-fraction times 12 equals minus 7.2 [pause] so B superscript prime equals open paren 9.6 comma minus 7.2 close paren [sentence pause] Based on the y-component values [pause] X is start-fraction 4 over 4 plus 7.2 end-fraction equals start-fraction 4 over 11.2 end-fraction equals start-fraction 5 over 14 end-fraction of the way from A superscript prime B superscript prime [pause] so X sub x equals 3 plus start-fraction 5 over 14 end-fraction open paren 9.6 minus 3 close paren equals start-fraction 75 over 14 end-fraction [sentence-pause] Therefore [pause] the base of X B superscript prime C superscript prime is the length of modifying-above C superscript prime X with bar [pause] which is start-fraction 75 over 14 end-fraction while the height is 7.2 equals start-fraction 36 over 5 end-fraction [pause] making the enclosed area equal to one-half the product of these two values [pause] start-fraction 1 over 2 end-fraction times start-fraction 75 over 14 end-fraction times start-fraction thirty 6 over 5 end-fraction equals start-fraction 270 over 14 end-fraction equals 135 over 7 end-fraction [pause] which needs to divided by 30 [pause] the area enclosed by A superscript prime B superscript prime C superscript prime [pause] start-fraction 135 over 30 times 7 end-fraction equals start-fraction 9 over 14 end-fraction [sentence-pause]”

“Given congruent right triangles A B C and A prime B prime, C prime, A equals the point 0 comma 5 [pause] B equals the point 12 comma 0 [pause] C equals the point 0 comma 0, A prime equals the point 3 comma 4 [pause] C prime equals the point 0 comma 0, and X is the intersection of the line segment A prime B prime and the x-axis. What is the area enclosed by triangle X B prime C prime divided by the area of A prime B prime C prime? The area enclosed by A prime B prime C prime is the same as that of A B C, which is 12 times 5 halves equals 30 units squared. The slope of C prime A prime is 4 thirds, so the slope of perpendicular C prime B prime is the negative reciprocal, or negative 3 fourths. The length of the line segment C prime B prime is the same as the length of C B, namely 12 units. Therefore, the coordinates of B prime are B prime sub x equals 0 plus start-fraction 4 over square-root of 3 squared plus 4 squared end-square-root end-fraction times 12 equals plus 9.6 and B prime sub y equals 0 minus 3 start-fraction 3 over square-root of 3 squared plus 4 squared end square-root end-fraction times 12 equals to minus 7.2 [pause] so B prime equals the point 9.6 comma negative 7.2. Based on the y-component values, X is start-fraction 4 over 4 plus 7.2 end-fraction equals to start-fraction 4 over 11.2 end-fraction equals to start-fraction 5 over 14 end-fraction of the way from A prime to B prime, so X sub x equals 3 plus 5 over 14 times open paren 9.6 minus 3 close paren equals 75 over 14 [sentence-pause] Therefore, the base of X B prime C prime is the length of the line segment C prime X [pause] which is 75 over 14 while the height is 7.2 equals 36 over 5 [pause] making the enclosed area equal to one-half the product of these two values: 1 half times 75 over 14 times 36 over 5 equals 270 over 14 equals 135 over 7 which needs to divided by 30, the area enclosed by A prime B prime C prime [pause] start-fraction 135 over 30 times 7 end-fraction equals start-fraction 9 over 14 end-fraction [sentence-pause]”

There are several ambiguities in the notation in the MathCounts problem. Three of them are:

These will be used to illustrate different ways of potentially resolving the ambiguity in that notation.

Common mathematical expressions such as

In general, math braille is presentational in that the braille describes the math that is seen, so problems with Presentation MathML are much fewer for braille generation. The MathML WG has identified three examples where braille is not presentational in Nemeth code (a common braille math code in the US and some other countries) inside of a mathematical expression.

The Web platform has support for a number of ideas related to some of our goals. We evaluate if they can be applied to MathML today, or could be extended in principle.

ARIA was designed to allow adding additional information to a tag when a tag does not convey the intended semantics/speech. Hence, it seems a natural approach to use for MathML to disambiguate a notation. However, there are a number of issues unique to math that make the use of ARIA problematic without changes to the ARIA spec.

The simplest approach to using ARIA would be to add aria-label to a math tag. For example, the point example above could be written as

<math aria-label="the point 0 comma 5">

<mrow >

<mo>(</mo>

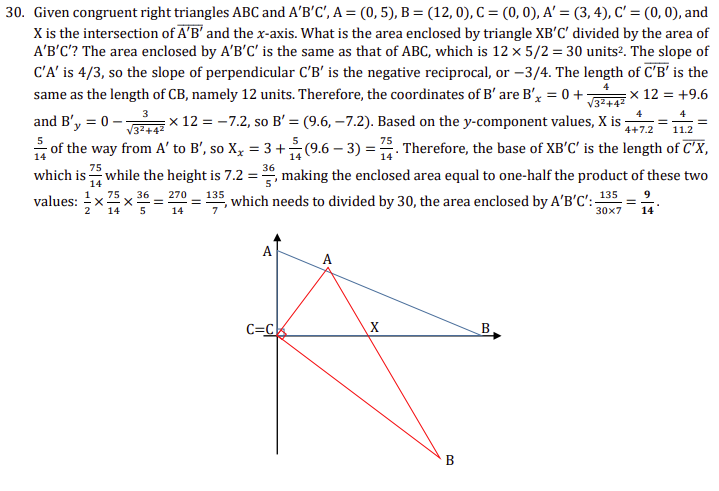

<mi class="arg1">0</mi>

<mo>,</mo>

<mi class="arg2">5</mi>

<mo>)</mo>

</mrow>

</math>

There are several problems with this approach:

| Long A | Short A |

|---|---|

This often makes the math unintelligible. Similarly, mathematical expressions have a different prosody than normal speech, so what is spoken is often harder to understand than it should be.

aria-label was rejected and it seems likely embedding special syntax for math will be acceptable. Ultimately, it should be the AT that decides what should be spoken; enough information needs to be passed to AT so it can present to a user what is best.maction, MathML elements are static elements. According to this blog, aria-label on static elements has poor support in many screen readers.Here is some potential markup using aria-label for the remaining two examples.

This example shows the need to use nested aria-labels.

<mover aria-label="the line segment A prime B prime>

<mrow>

<msup aria-label="A prime">

<mi>A</mi>

<mo aria-label="prime">′</mo>

</msup>

<mo>⁣</mo>

<msup aria-label="B prime">

<mi>B</mi>

<mo aria-label="prime">′</mo>

</msup>

</mrow>

<mo>¯</mo>

</mover>

This is similar to the line segment example in terms of complexity. Note that the second argument is spoken first.

<msub aria-label="the x coordinate of the point B prime">

<msup aria-label="the point B prime">

<mi>B</mi>

<mo aria-label="prime">′</mo>

</msup>

<mi>x<mi>

</msub>

As noted above, a downside to using aria-label is that it is very repetitive: every parent element must include the text used in the child. An appealing alternative is to use multiple aria-labelledby ids instead of aria-label, where the value of aria-labelledby points to the various children. These in turn can point to their children. The problem with this approach is that text can not be mixed in with the ‘id’s used in aria-labelledby so that a square root does not have a child to point to for the “square root of” part of the expression “square root of x plus y”. A few (unpleasant) hacks are possible by introducing elements that don’t display and adding aria-label to them, but this seems like a poor solution. The unit circle example below illustrates the use of aria-labelledby:

<math aria-labelledby="ex2">

<mrow id="ex2" aria-labelledby="point varname at-coordinates">

<mrow id="point" aria-label="point"></mrow>

<mrow>

<mi id="varname">X</mi>

<mrow id="at-coordinates" aria-labelledby="coordinates x y">

<mo stretchy="false">(</mo>

<mn id="x">0</mn>

<mo id="coordinates" aria-label="at coordinates">,</mo>

<mn id="y">5</mn>

<mo stretchy="false">)</mo>

</mrow>

</mrow>

</mrow>

</math>

A number of issues surrounding the use of aria-labelledby are explored in this prototype. Additionally, the prototype explores the use of aria-describedby to add additional information such as a variable being a natural number, something you would not want to hear in a full reading of an expression.

Many of the ideas listed in this document deal with ways to expressing relationships in the tree and providing annotations in order to provide rules about the intended semantics of markup. While this problem is distinct from visual styling, it is difficult to not see relationships with the architecture CSS, or things defined by it. CSS Selectors, for example, are the platform standard for “selecting” and associating elements in the DOM tree, even outside of stylesheets. It is not difficult to imagine exploring a “CSS-like” language which could meet general needs by providing sheets of rules and properties re-using the architecture of CSS to supply supporting annotation expressions.

Today it is possible (assuming we determine a way to pass to AT that is acceptable, like using aria-label) using CSS Custom Properties and a very little JavaScript for us to begin to explore these ideas defining properties like ‘–speech’ whose values are expressive and evaluated during lifecycle events that we define. An example of this today might look like:

<mrow data-intent="point">

<mo>(</mo>

<mi class="arg1">0</mi>

<mo>,</mo>

<mi class="arg2">5</mi>

<mo>)</mo>

</mrow>

[data-intent="point"] {

--speech: "the point " text(.arg1) " comma " text(.arg2);

};

A codepen shows how this might work. The sample codes adds an aria-label to an element with the attribute data-intent based on the stylesheet.

Mathematical structures are commonly nested inside one another. If the class values are not uniquely named for each data-intent, they will likely end up interfering with a selector.

There are many ways to represent equivalent MathML expressions. The CSS selector method requires that the authoring software generate MathML with data-intent values and class values that match a CSS stylesheet. Hence, it is likely that unique CSS stylesheets will be required based on the MathML authoring software.

This example shows the need to use multiple classes to deal with nested structure.

It also illustrates that the value of an argument might itself require computation of the data-intent.

<mover data-intent="line-segment">

<mrow>

<msup class="start" data-intent="modified-identifier">

<mi class="base">A</mi>

<mo class="modifier">′</mo>

</msup>

<mo>⁣</mo>

<msup class="end" data-intent="modified-identifier">

<mi class="base">B</mi>

<mo class="modifier">′</mo>

</msup>

</mrow>

<mo>¯</mo>

</mover>

[data-intent="line-segment"] {

--speech: "the line segment " text(.start) " " text(.end);

}

[data-intent="modified-identifier"] {

--speech: text(.base) " " text(.modifier);

}

This is similar to the line segment example in terms of complexity. Note that the second argument is spoken first.

<msub data-intent="point-coordinate">

<msup class="point" data-intent="modified-identifier">

<mi class="base">B</mi>

<mo class="modifier">′</mo>

</msup>

<mi class="coord">x<mi>

</msub>

[data-intent="point-coordinate"] {

--speech: "the " text(.coord) "coordinate of " text(.point);

}

This approach can be used to define both “UA” style rulesheets which require no author provided rules at all for many cases, but allows them for extension. The trouble with such a solution is that it does not itself belong in CSS, but merely wants to reuse its architecture. The Houdini Task Force’s work is particularly interesting here: its aims include making it possible to reuse the architecture of CSS to develop CSS-like languages. Some progress has already occurred: the CSS Parser and Typed Object Model are part of Chrome and Edge. It would be especially helpful to coordinate with and be sure our use cases and examples are considered, and gaps and concerns with the approach identified.

Practically speaking, if aria-label is used as the output of the speech property, such an approach might include very few new MathML specific asks of the platform. Mainly some changes to aria-label such as allowing some control over speech and adding an exception to the requirement that AT braille the text in aria-label). There is still the problem of knowing the needs of a user so that appropriate speech is generated. User-stylesheets are a potential solution, but they come with their own set of problems.

Schema.org is an ongoing effort developing vocabularies for aiding “Rich Results” in information retrieval, endorsed by most major search engines. It can be deposited via each of Microdata, RDFa, or JSON-LD, which allow parallel annotation on top of MathML expressions. Hence, in theory, using schema.org could be a carrier for our intent annotations. We did a basic evaluation, with the first goal of exposing the deposited information for search.

We embedded RDFa in an HTML page which was successfully collected by web crawlers. However, we couldn’t find schema.org vocabulary entries which could carry our “intent” information to the result pages of major search vendors. For example, we tried to use “disambiguatingDescription” and “name” on both MathML token elements as well as HTML span elements. There may be a better approach but our initial experiment was not successful.

We invite those with more experience with RDFa to contribute suggestions on how it can be used to pass information to AT.

The MathML standard includes elements to describe the visual presentation of an expression, and elements to describe the functional content of an expression. These two subsets of MathML can be used independently, or combined using the MathML <semantics> element.

The

<semantics>

<mrow id="x">

<mo id="x.1">(</mo>

<mi id="x.2">0</mi>

<mo id="x.3">,</mo>

<mi id="x.4">5</mi>

<mo id="x.5">)</mo>

</mrow>

<annotation-xml encoding="MathML-Content">

<apply xref="x">

<csymbol>point</csymbol>

<cn xref="x.2">0</cn>

<cn xref="x.4">5</cn>

</apply>

</annotation-xml>

</semantics>

Content MathML has a few methods to associate meaning with a csymbol. One method is to use one of the ~140 predefined symbols. Neither point nor the other csymbols used in the examples are one of the predefined symbols.

However, external dictionaries provide extensibility. For example, the definitionURL attribute could refer to the Wikidata definition of point (link); alternatively the cd attribute could refer to an OpenMath Conent Dictionary.

For simplicity, those are omitted in the examples in this section. One possible source of definitions that might be able to be used to associate speech with a definition is Wikidata (see this paper for more information). For example, the Wikidata definition of “point” is here.

ci and can contain presentation MathML as illustrated in the example below.

<semantics>

<mrow id="e">

<mover id="e.1">

<mrow id="e.1.1">

<msup id="e.1.1.1">

<mi id="e.1.1.1.1">A</mi>

<mo id="e.1.1.1.2">′</mo>

</msup>

<mo id="e.1.1.2">⁣</mo>

<msup id="e.1.1.3">

<mi id="e.1.1.3.1">B</mi>

<mo id="e.1.1.3.2">′</mo>

</msup>

</mrow>

<mo id="e.1.2">¯</mo>

</mover>

</mrow>

<annotation-xml encoding="MathML-Content">

<apply xref="e">

<csymbol>line-segment</csymbol>

<ci xref="e.1.1.1">

<msup> <mi>B</mi> <mo>′</mo> </msup>

</ci>

<ci xref="e.1.1.3">

<msup> <mi>B</mi> <mo>′</mo> </msup>

</ci>

</apply>

</annotation-xml>

</semantics>

This is similar to the second example in that ci.

<semantics>

<msub id="f">

<msup id="f.1">

<mi id="f.1.1">B</mi>

<mo id="f.1.2">′</mo>

</msup>

<mi id="f.2">x<mi>

</msub>

<annotation-xml encoding="MathML-Content">

<apply xref="f">

<csymbol>point-coordinate</csymbol>

<ci xref="f.1">

<msup> <mi>B</mi> <mo>′</mo> </msup>

</ci>

<ci xref="f.2">x</ci>

</apply>

</annotation-xml>

</semantics>

The <semantics> element has been part of the MathML standard since 1998, so no new technology is needed to support this solution. Despite being present since MathML’s inception, content markup is only rarely used in web pages, electronic documents, or math authoring tools; parallel markup is used even less frequently.

Each of the solutions above have problems when applied to math. This has led the group to explore a new MathML-specific solution. The largest drawback to any MathML-specific solution is that it would expand any “MathML exists in its own world” criticism and wouldn’t leverage work done on the web to support existing web technologies, now or in the future. The generic advantage is that the solution would (mostly) not be held hostage hoping for changes to other specifications.

We have decided to use the term intent to refer to the mathematical meaning conveyed by an author using presentation MathML. It is meant to offer a lightweight solution for partial annotation of an expression so it can be spoken appropriately by AT. The intent syntax borrows concepts from Content MathML to encode the structure of mathematical operations (an “operator tree”), allowing for incremental narration and navigation that follows the argument structure of a formula.

One proposal is to introduce a MathML-specific intent attribute, whose value encodes a functional expression composed using a vocabulary of function symbols (e.g. binomial-coefficient, factorial, sine, open-interval, …) applied to references to descendent subtrees that act as conceptual arguments in a mathematical expression.

Such an attribute could be used by an authoring tool, for example, to encode the point (0,5) as the expression point(0,5) as follows:

<mrow intent="point($1,$2)">

<mo>(</mo>

<mi arg="1">0</mi>

<mo>,</mo>

<mi arg="2">5</mi>

<mo>)</mo>

</mrow>

If (0,5) had another meaning, such as an open interval, or an ordered pair, or greatest common divisor, a value other than “point” would be used in the intent attribute.

Here is some potential markup using intent for the remaining two examples.

This example shows the need to use nested intents.

<mover intent="line-segment($1,$2)">

<mrow>

<msup arg="1" intent="A-prime">

<mi>A</mi>

<mo>′</mo>

</msup>

<mo>⁣</mo>

<msup arg="2" intent="B-prime">

<mi>B</mi>

<mo>′</mo>

</msup>

</mrow>

<mo>¯</mo>

</mover>

This is similar to the line segment example in terms of complexity. Note that the second argument is meant to be spoken first, where one could imagine a “speech rule” of the form the $2-coordinate of $1, associated with the coordinate value and that intent values without parameters are typically spoken verbatim.

<msub intent="coordinate($1,$2)">

<msup arg="1" intent="B-prime">

<mi>B</mi>

<mo>′</mo>

</msup>

<mi arg="2">x<mi>

</msub>

Various proposals have been discussed for the syntax to be supported by the intent attribute, with varying trade-offs in markup convenience. One proposal is to include default intent values for existing MathML presentation forms and default names for math operators to reduce the amount of markup needed to specify the intent of an expression. For example intent but would be equivalent to a version that included intent="factorial($1)" on the mrows in the fraction, etc. While the full encoding of the content markup for an expression is often complex, and often not included with the presentation, the inclusion of the intent markup for an expression is potentially much simpler to generate and easier to consume, as part of the presentation markup.

An advantage of this proposal is that it can be implemented using current technology without changes to other web standards, other than to specify that the attribute should be part of the accessibility tree built by browsers. While the functional syntax [‘name(arg1, …)’] represents a MathML-specific encoding, it is relatively easy to generate and to consume.

The intent attribute is meant to be passed to AT. This allows AT to decide what is appropriate, based on the needs/preferences of the reader. It avoids the problem of having to know whether to embed in aria-label speech geared to someone who can’t see the screen (and hence needs begin/end cues) or geared to someone who can see the screen and needs audio reinforcement to help them decode what they see. As intent annotations work together with the presentation tree, they enable AT to add prosody cues, e.g. forcing a long ‘a’ sound for a variable named ‘a’. That is something which currently can’t be done with aria-label.

Considerable investigation is underway to collect names of math concepts and operators, when they are associated with dedicated notational conventions. The group is also exploring common presentation markup patterns which could be prescribed a “default interpretation”, so that AT could assume an intent value over their classic, unannotated, MathML 3 tree. Elementary math examples can often be made accessible using only such default rules, and many intermediate examples can be handled by only encoding ambiguous operators and their arguments. Even more complex examples such as integral forms where the differential appears as part of the expression for the integrand can be properly separated into their constituent parts and indexed into via the associated arg attribute.

Providing a subject area attribute such as subject="geometry" is an adjunct to intent and default idea.

Each defined subject would include a list of notations and their default intent value.

This could provide a simpler means of remediating a document in some cases.

For example, a publisher might add a subject area to all the math tags in a geometry book so that the default intent of intent="point($1,$2)". The three examples used in this document could all be captured by adding subject="geometry" to the math tag. The use of subject to indicate “chemical-formula” is particularly useful for chemistry, where superscripts on elements represent ions not powers; subscripts on chemical elements aren’t pronounced (e.g.,

The Math WG has not had detailed discussions about using subject areas yet. If the idea works out, it is likely that at least initially, the number of known subject areas would be limited to perhaps as few as 5–15 subject areas covering basic math and science areas. The number of changes each subject area would make to the generic defaults is very dependent on the subject area. Potentially more than one subject area could be given with conflicts resolved by order. As with intent, subject area can be implemented without changes to other web standards other than needing to be part of the accessibility tree. At least one AT tool (MathPlayer) makes use of user-specified subject areas to override defaults on what is spoken, so there is a little experience with this concept. Classifying mathematics and other sciences is difficult. It is unknown if a broad brush categorization approach to K-14 topics as currently envisioned is feasible; this remains to be investigated if using intent is pursued further.

This document was a group effort by many members of the Math WG as part of an ongoing internal conversation.